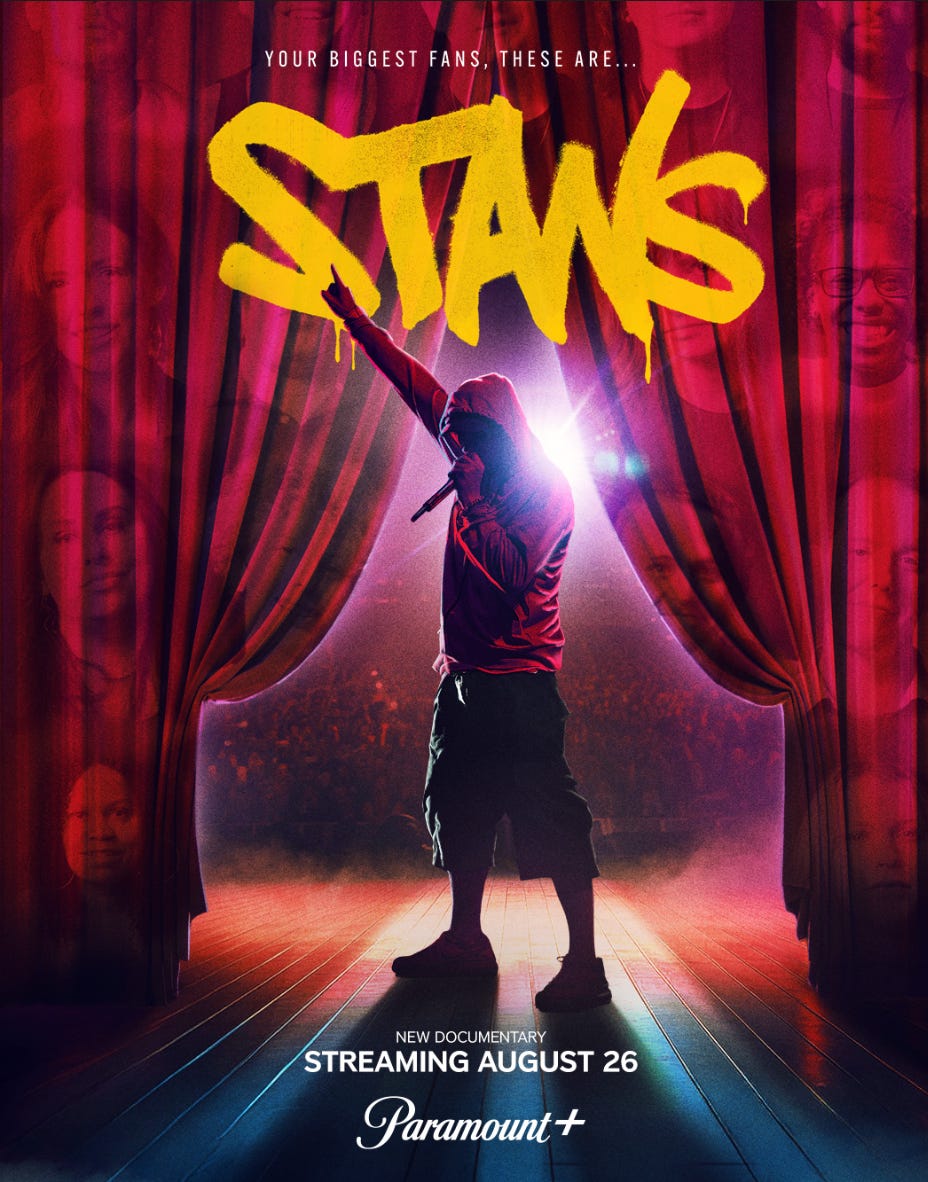

'Stans' and 'Vice is Broke': Two new documentaries about transgressive things from the early 2000s

Both debuting on streaming this week, the two docs take very different approaches.

It’s very easy to imagine Eminem being the subject of a great documentary by a serious documentarian. It would look at where he came from, his rise to fame, all his controversies, and — possibly most intriguingly of all — what it’s like for a guy like him to reach his 50s. How does he look back on his old work today, and especially the anger of it? Does he have any regrets?

Eminem’s own story is a fascinating one: He burst on the scene in 1999, a rare white rapper who earned credibility right out of the gate. He was controversial, for lyrics that included everything from rank homophobia to threatening his own mother. After several hit albums within a short period, he starred in the acclaimed Purple Rain riff, 8 Mile, in 2002.

In the following years, he suffered from addiction and other troubles, although he has continued to make music, and appears to be in something of a good place in his life, at age 52.

The new documentary Stans, very much, is not that.

Stans is focused on about a dozen people who are real-life superfans of Eminem. While they all have stories about the performer getting them through tough times, their fandom is of various degrees of healthy and not-so-healthy. Unlike their lyrical counterpart, it doesn’t appear any of these people have ever been inspired by the rapper to do anything violent, although one guy does admit to some light stalking, and others apparently are using their parasocial relationships with the rapper to fill in other voids of their lives.

Sure, there’s a light bit of tracing Eminem’s career arc, but the film is mostly about his fans, and none of the fans are especially interesting.

Nevertheless, Stans at its core, it’s a documentary produced by Eminem’s production company, which is primarily about how Eminem is awesome and Eminem’s fans all think he’s awesome. This is PR and brand maintenance, not documentary.

It starts with that term itself, “Stan.”

The Eminem song “Stan,” which came out in 2000 around the beginning of his career, is about an obsessed fan of the rapper who writes him letters of escalating intensity — including an admission of homosexual longing for Eminem — until Stan locks his pregnant girlfriend in the trunk of a car and drives off the road.

Among other things, the song brought the term “Stan” into the lexicon, as well as the dictionary. The term can have positive or negative connotations, depending on the context, but it usually refers to an obsessed fan who implicitly has an unhealthy parasocial relationship with the famous person in question.

There’s almost no attempt to reconcile the rougher, more controversial sides of Eminem’s persona with the soft-focus portrayal we see here. Those violent anti-gay lyrics in some of the rapper’s early music? It might have been good for the film to at least address that, especially since at least some of the fans interviewed are of the LGBTQ persuasion.

There are some half-assed complaints about occasional social media flareups, when younger people discover old Eminem lyrics and declare “they’re trying to cancel Eminem!” As if that in any way compares to the cultural uproar that greeted Eminem back in 1999 and 2000- when the result was his career continuing to rise.

Stans got a theatrical release earlier this month that comprised of a single weekend, with not a lot of promotion, and now it’s streaming on Paramount+.

For the most part, the documentary chronicles the journey of Eminem, over about 25 years, from transgressive bad boy to syrupy, inspirational figure. The old Eminem, alas, was way more interesting.

Around the same time Eminem was shocking the world with his early albums, the media company known as Vice was doing the same thing, across multiple forms of media.

Really, Vice had several different eras, although some of them overlapped: It began in Montreal in the late 1990s with a magazine of the that name, which regularly offered shocking and often hilarious stuff, from sex guides to transgressive racial humor, most notably in the Do’s and Don’ts column.

Around the turn of the Millennium, the company moved to New York, and eventually branched into video content. I lived in New York during that period and read the magazine, but wasn’t anywhere cool enough to be associated with that scene. This interview of the founders by New York Press, I believe from 2000, is a super-fascinating time capsule.

For a while, “Vice” was mostly associated with third-world travelogue documentaries, in which its reporters filmed themselves in dangerous places.

As the 2000s wore on, Vice started to gain ambitions to become a global media conglomerate, which included a news channel, investments from Disney and A&E, and a “content marketing” studio, which did work for such unsavory clients as Philip Morris and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Vice also ran a Gawker-style website that did left-leaning investigative journalism. At its peak, the company was worth billions on paper.

Then, in 2023, the company declared bankruptcy and stopped publishing web content. The company still exists in some form — with cofounder Shane Smith allegedly trying to revive it — and Vice is still a cable channel, one I only ever think about when it’s time for a new season of Dark Side of the Ring.

Now, Eddie Huang, the chef, author, and TV personality who worked for Vice for many years, has directed and fronted a documentary called Vice is Broke, which tells that whole story, or at least his version of events.

It’s a very entertaining look back at an extremely colorful company, one that probably everyone involved in would probably admit has a powerful but mixed legacy.

At the same time, it’s very clear that Huang has a very specific axe to grind here, and grind it he does.

Huang, as he makes clear in the doc, is essentially a professional non-seller-outer. Any project he feels isn’t true to his vision, he’s happy to walk away from, whether it’s the sitcom adaptation of his memoir Fresh Off the Boat, or his past involvement with Vice. And that even extended to Vice is Broke itself: Huang, upset with Mubi for taking money from the same investment fund that invests in Israeli weapons, has vowed not to promote the film’s debut.

One aspect that’s hard to get away from: Among the cofounders of the company was Gavin McInnes, who left Vice in 2008, became a right-wing pundit, and went on to found the Proud Boys. Even going back to the company’s early years, McInnes — who is interviewed in the film — has either been a virulent racist, sexist and homophobe, or has made a career out of trolling people into thinking he’s all those things.

However, he’s not the Vice cofounder who Huang is mad at. That would be Shane Smith, who Huang and several other Vice veterans interviewed in the film, blame for selling out the company’s vision and potential over the course of many years. Also, as is mentioned repeatedly, he owes Huang a bunch of money for past residuals.

That’s probably all true, and the film lays out a convincing case of what caused Vice’s downfall, along with other factors, including changes in how traffic is allocated on the Internet, and the simple notion that Vice’s identity was based on being cool, and that’s a hard thing to keep up forever. Michael Moynihan, another former Vice employee, has made the "go woke, go broke" case for the death of Vice, although Moynihan was more artful than most in making that argument.

But I don’t know, I think the cofounder who founded a fascist militia that widely participated in a seditious conspiracy is a bit more worthy of scorn than the one who mismanaged the company into bankruptcy.

McInnes isn’t the only controversial figure interviewed in the film; Huang also drags out comedian Joshua “The Fat Jewish” Ostrovsky, a guy I forgot even existed. And everybody’s favorite social media journalist, Taylor Lorenz, is interviewed as well.

Huang, in the film, is especially tough on those Vice documentaries, which he attacks for everything from exoticism towards the third world, to failing to credit directors. Huang makes clear that he idolized Anthony Bourdain, and the Vice docs were the anti-Bourdain, as the doc points out- Vice would visit foreign countries and point out how scary they were,while Bourdain was more about finding love, value and vibrancy everywhere.

We’re shown the famous documentary scene where the New York Times’ David Carr dressed down founder Shane Smith, "Just because you put on a fucking safari helmet and looked at some poop doesn't give you the right to insult what we do.”

The doc, though, leaves out the great Documentary Now parody, in which Bill Hader and Fred Armisen kept playing reporters who died violently, and were replaced by different reporters, also Hader and Armisen, in slightly different costumes.

Huang says himself, in the movie, that someone he could see someone like Alex Gibney making a more straitforward documentary about the fall of Vice, the way he previously did about the collapse of Enron. I certainly appreciate the perspective Huang brings, but I’d probably like to see a more conventional take alongside it.

Stans is streaming on Paramount+. Vice is Broke lands on Mubi on Friday, August 29.

Check your spelling on the first bankruptcy.